Only the luckiest grrls get two mothers.

A couple weeks ago, I bought my plane ticket for my annual sojourn to see my family and homies over in Germany and Switzerland. I love, love, LOVE being able to go over in the springtime; there’s something uniquely liberating about spring in Europe, the contrast to winter, the light and lightness that comes in so quickly, it takes your breath away. But in the days after buying said ticket, I found myself getting irritable and annoyed, melancholy and downright sad. Ugh. Grief was back.

Last fall, the day after Thanksgiving, my German mama passed away. Typing those words, I feel such an overwhelming anger at the unfairness of their truth. I am not yet willing to accept that this Earth doesn’t hold her human form anymore. It’s been 5 months, but now that I’m making my plans for my annual visit, because of the memorial service we’re holding for her, it’s all flooding back in. I do not want this. I do not want a world in which I don’t land in, or depart from, spending time with her. She’s provided me with an utterly welcoming—and sometimes challenging!—spot to exist since I was 17 years old. Thirty-odd years of having a chosen mom, in addition to your already-brilliant mom who gave birth to you and raised you, is not enough. It’s just not.

Once again, I would like to speak to a manager about things, please.

When Mama passed away, I wanted to write down everything I knew about her and blast it out to the world. I wanted to force everyone I had contact with to reckon with the loss of such a force of a human, I was so angry and heartbroken. (Still am, obviously.) But when I went to put my anger into words, those words remained out of reach, like I was a magnet with the wrong pole facing their magnets, pushing them away. I’m trying to be better about recognizing that kind of thing, that it’s not the right time to create something when that happens. I sat with the grief, mostly on my own.

And now this stupid plane ticket is making me cry.

I spent this past weekend with my mom, who also knew Mama and loved her, and admired her, dearly. I told her how much it all hurt and that I didn’t want this to be real. It all bubbled right on up and over the top, pouring out in tears and snot, and I could hear Mama trying to soothe me. “Ach, Schätzchen…” I decided I’d try to move through some of it with a post to you all sharing a bit about my adventures with Mama.

Here’s how it all started.

Back in 1991, when I was in 11th grade, we had a German exchange student show up in our school. Her name was Ljerka, and she was having a tough time with the family she was placed with. I figured she could move in with us! My family was always on the lookout for a good stray human to take in, and we had an extra bedroom because my brother had joined the Air Force a couple years before. Plus, we’d just been to Germany for the first time that year, visiting my dad’s family, and I had fallen in utter and total love with the place. Right after Christmas, Ljerka moved in with us. We became an instant family—to give you an idea, spoiler alert, my dad walked her down the aisle when she got married 17 years later. When Ljerka moved in, I confessed to her that I wanted to be an exchange student to Germany.

“Well, you should just come live with my mom and my little sister and brother next year,” she said, in her uniquely matter-of-fact way that somehow could make even the most outrageous schemes make sense. We presented this idea to my parents, who promptly said no. With a voice that came from seemingly nowhere, I asked, “Why not?” This was not a question that we asked in our family. Answers were answers, and rules were rules. Questioning them was not an option. But by then, I had spent enough time with Ljerka, who saw opportunity everywhere, who questioned all kinds of things that blew my mind, who saw ways around and through challenges like no one I’d ever met before. Her M.O. was not to rebel or protest, but to maneuver with confidence, knowledge, responsibility and skill. I’d never met anyone like her.

My mom remembers hearing my “why not” and not having an answer, and then being immediately startled by not having an answer. She reenacts that moment now when you ask her about it, remembering that she elbowed my dad and said, “Gus… tell her why not.”

Somehow we started hammering out the deal. When Ljerka was graduating from our high school that June, her mom, my soon-to-be-Mama, came over, and the parents conferred. My mom now says that she had already admired Mama from the times they’d talked on the phone, but when they met in person, that’s when she knew that she could send me over to her.

So, the following August, without an official program or a real plan in my head, I went over to Germany to live at 17 years old. (OK, the backup plan was that my dad’s family is there and lives not that far away, so there would at least be that in the country, if things went horribly wrong.) And Mama took me in, and basically made me her project.

In the years since, we’ve laughed about the big moment that stood out to her as to what she’d taken on when she agreed to this scheme. The year that I was there, Ljerka was living in a different city to finish her schooling. She’d come home on the weekends pretty regularly, and one time, when she was heading back to school, we were late getting her to the train station. I didn’t yet speak German, but she and Mama explained to me in English that I should take Ljerka’s luggage and go to the train platform, while they ran into the station and bought the ticket. They would meet me on the platform, where she’d jump on the train and we’d throw her luggage in after her.

Except, I didn’t know how to find the platforms. I didn’t even know the word for “platforms,” and this was 1992, before Germany put a lot of signs in English in their transportation hubs. I’d never actually been to a train station before, so I didn’t even know where to begin to look. Mama and Ljerka eventually found me, after the train had left, panicking in the underground area of the station, lost beyond words. They were frustrated with me, and I burst into tears. I didn’t know how to do the thing, and I also wasn’t good at not knowing how to do a thing. I blubbered, “I looked and looked but I’m just totally confused!”

Mama said that she realized at that point that she had a big job in front of her, haha.

That phrase, in English, has remained with our family to this day. I’m giggling thinking about all the times we’ve all been speaking German and have said things like, “Ja, dann bin ich zu meiner Mitarbeiter gegangen, und hab gesagt, ‘du, ich bin doch totally confused.’”

What she wanted me to learn most that year (besides German without a regional accent/dialect, har har) was self-accountability. She wanted me to learn to make my own choices and to live with the consequences of those choices. Before this, the more American style of child-rearing (or what I imagine to be American) was the model that I lived by. In that model, there was always some external authority that I had to be accountable to: my parents, my teachers, God, whomever. Mama wanted to be accountable to myself, and to be able to live with myself.

The liberation that has come from that structural shift has had so many ripple effects in my life, I can’t even begin to describe them. I don’t know who I would be now without it. To start to turn from trying to figure out what everyone else wanted from me, to learn what I wanted from me, and to spread justice and joy through that… It’s still a work in progress, Mama, but I’m getting there.

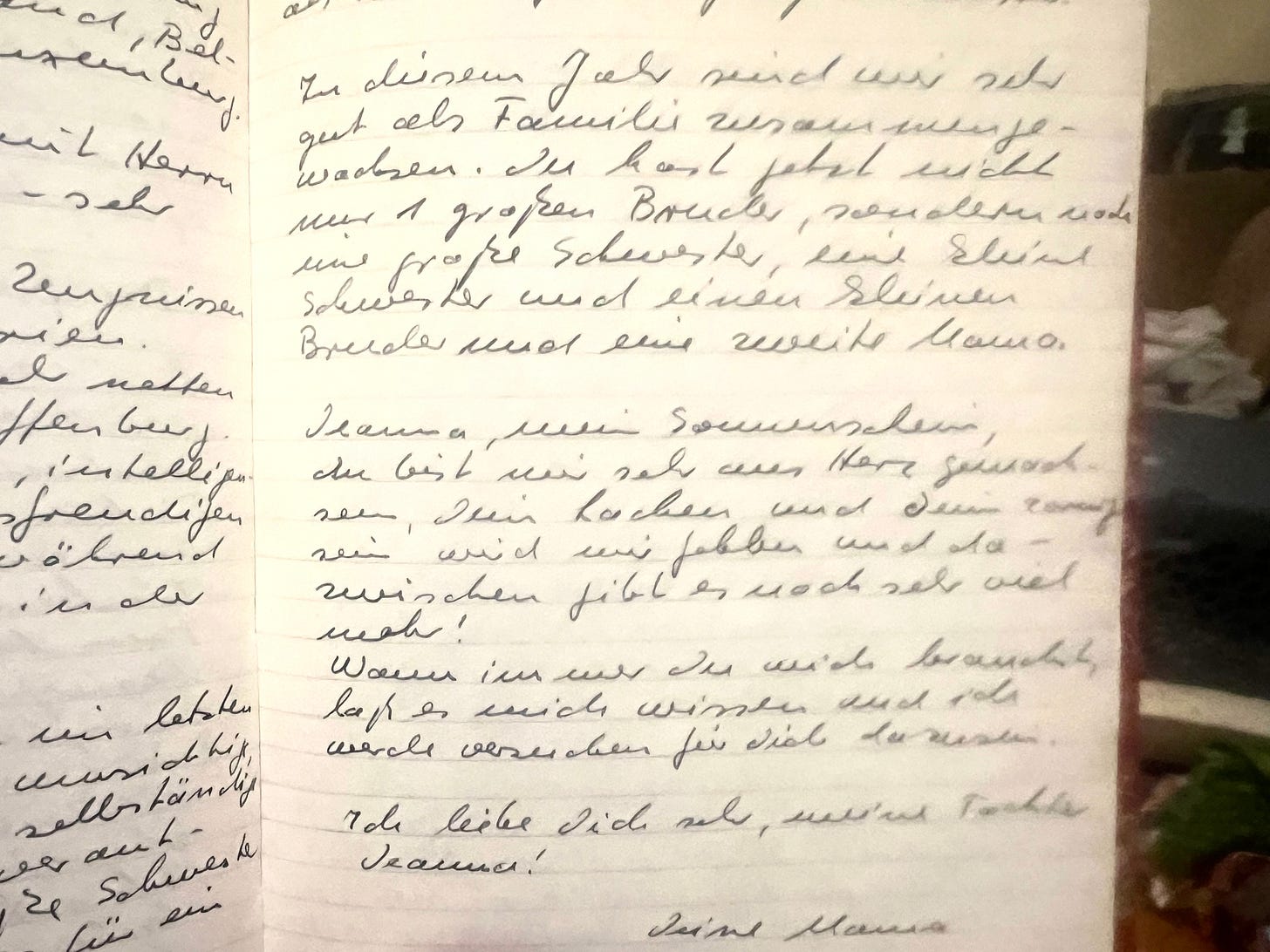

When I left Germany a year later to try to resume an American life that would never be the same, she suggested I get a book and have people write me goodbye notes in it. She wrote me the longest one, and ended with, “In this year, we grew together as a family very well. You now don’t just have one big brother, but also a big sister, a little sister, a little brother, and a second Mama.”

It wasn’t until years later that I learned about the concept of “chosen family” from queer communities, and I understood immediately what it meant to meet people, to live through things together, and to know that you would be bound for life. I never have had to separate from my family of origin, so I’ve got bonus family. My sisters and my brother over there, and now my sisters-in-law (one who is chosen family, too!) and my brother-in-law, my nieces and nephew, they continue to make me who I am. Even when we’re all totally confused, the fresh air will keep us healthy. But that’s another story for another time.

“To start to turn from trying to figure out what everyone else wanted from me, to learn what I wanted from me, and to spread justice and joy through that…”

What a beautiful lesson. I’ll be taking this one with me.

I hope the notebook is a comfort to you. What an incredible woman!

Lucky to have had such abundance. Grief, the price of love. The Buddha is alleged to have said “Take what you want and pay for it.” Such a high price, worth it