"You are worth so much more than your productivity."

On "quiet quitting" and other work-related nonsense

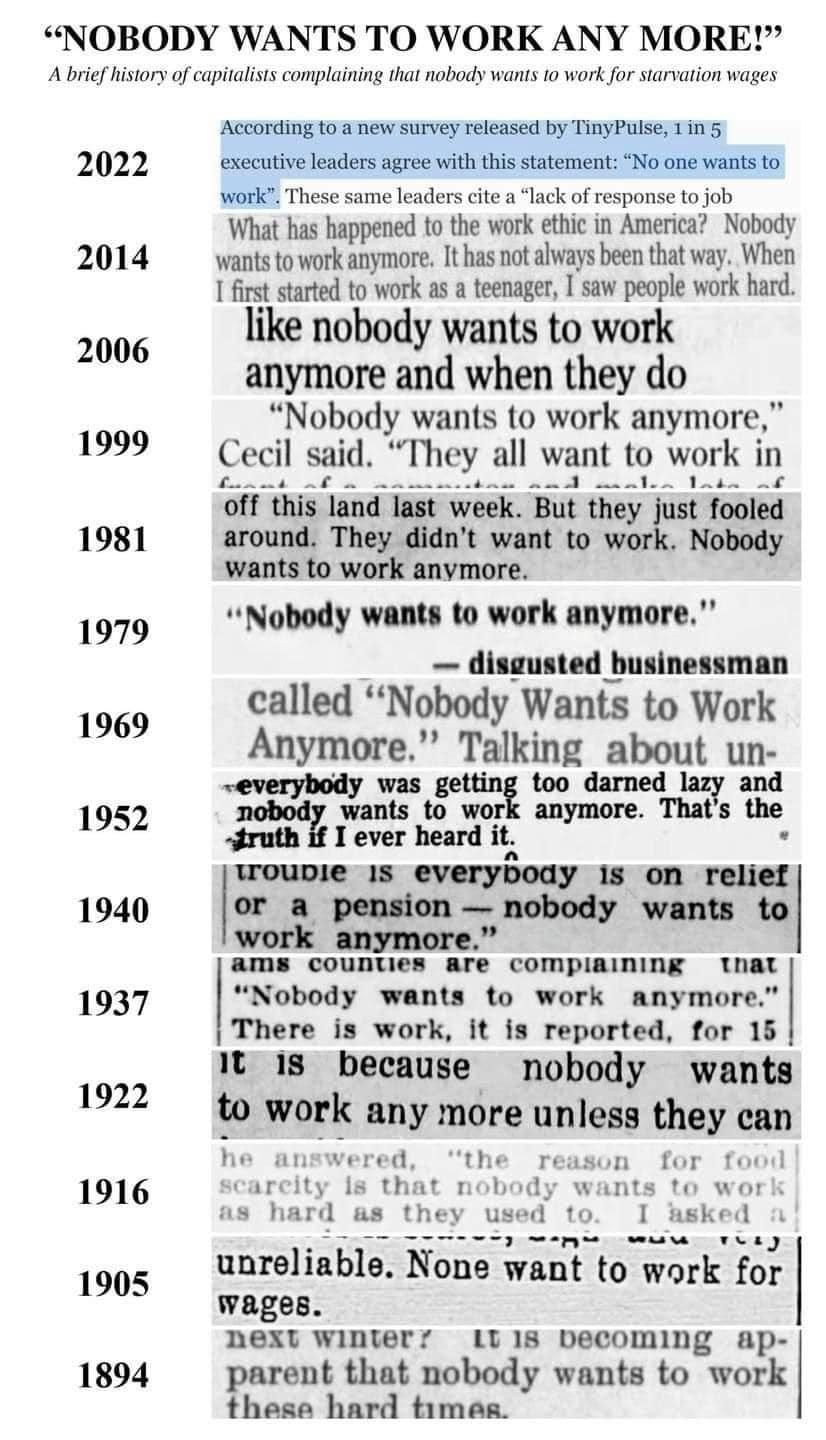

I saw this card randomly online probably 10 years ago, and it kind of blew me away. I had never, until that moment, considered how much of my self-worth I had placed on what I was able to do, or produce, or help with. And it's been right at the forefront of my brain as we've been hearing about all kinds of work "trends" that have been cropping up—"quiet quitting," "no one wants to work anymore," etc. If you haven't heard about it, "quiet quitting" is when you stop doing tasks outside of the job you were hired for, but don’t say that you’re doing so. (This is often because things got piled onto you without your consent to begin with.) And the whole "no one wants to work anymore," don't even get me started on that one. Someone researched how long this phrase has appeared in media, and it turns out, people who have been comfortably living off of others' labor have been saying this kind of thing for decades.

"Time is money."

No, time is an illusion! And money is made up! Arrrrrrgh!

I was just looking over the Wikipedia entry for the book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism by Max Weber, written in the early 1900s. There's loads to unpack, but this passage that the entry cites stood out to me:

"Remember, that time is money. He that can earn ten shillings a day by his labor, and goes abroad, or sits idle, one half of that day, though he spends but sixpence during his diversion or idleness, ought not to reckon that the only expense; he has really spent, or rather thrown away, five shillings besides. [...] Remember, that money is the prolific, generating nature. Money can beget money, and its offspring can beget more, and so on."

I think about how insidious of a concept this has become, how infected our systems and cultures are with it. In this oversimplified version of the equation, there are no other considerations or values that one should take into account when choosing how to spend one's time. Resting, care, absorbing beauty, thinking, enjoying oneself, none of those very basic needs gets accounted for. The only truth is that time is money.

The other craptastic part of this is that it also assumes all playing fields are level, and that if one just works hard enough, money will appear. That's almost as bad as the ”manifesting” baloney I wrote about last time. Hard-work-will-set-you-free assumes that people will always be paid, and paid fairly/equitably, and paid on time, and and and, for the work that they do. Turns out, not so much.

But let's go back to other ways that this has infected us.

First, let's look at "idleness" as a concept. I'd argue that there's no such thing as idleness— an former therapist reminded me often that "sitting is also an action." When you're still, you're: resting, thinking, staring, listening, observing, breathing, scratching, dozing, all kinds of stuff is going on. So, you're not actually ever idle. (Unless you're an enlightened being who's manage to get to emptiness, of course. I am not talking to you. For many reasons, mostly that I'm jealous. Anyhoo.)

Second, the demonization of "idleness" is also kind of wild. Look at that book excerpt above: by sitting still, you have actively thrown money away. And since in capitalism, there is no greater drive than accumulation of money so that it can beget more money, this is a pretty big sin. If you are not physically producing evidence of labor, you are not signifying to the rest of the world, or to yourself, or to God, that you are participating in the system we've all supposedly agreed works really well. You're not a team player.

And that in turn leads to a lot of shame and guilt that we put on ourselves. We've swallowed this perception of idleness-as-demon for so long, since we were wee tiny babies, and we feel the internal repercussions of it almost daily. On OKCupid, there's a question in their matching system that says, "If you don't do anything for a whole day, how do you feel?" There are only two choices: "good," or "bad." I have yet to see anyone else answer "good" in my time there. It is accepted that this is a bad feeling, to have not "done" anything—even though, as per above, there's no such thing—to not have anything to "show" for that whole day. You didn't clean your house! You didn't finish that assignment! You didn't go anywhere, see anyone, or have any fun, even! You're not doing it right! Did you earn your right to exist today by doing something?!

I always think about this moment at Christmas with my family from a few years ago— we were finished opening our presents, and had settled into spots around the living room to drink coffee, read our new books, look at instruction manuals, etc. I found myself getting sleepy (shocking no one), and just as I was thinking about getting up to go take a nap, my mom popped up out of her chair saying, "Whew, I got sleepy! I gotta get moving!" I started laughing and told her that I'd had an entirely different reaction to feeling sleepy.

Idleness breeds all kinds of other openings for figuring how to exist in a version of the world that wants to extract every last drop of everything for us. It's when our ideas swim around in our brain goo, when we process our experiences and dreams, when we get rest for the next thing we'll need our energy for. This is especially true for creative people—every artist I know has shamed themselves at some point for not "working," and we all forget that the swishing of the goo and the resting of the body is part of the work. Mind you, I'm also writing this because I'm reminding myself that my lack of words or doodles on paper lately is OK, and to not be hard on myself for it. It's hard to internalize that message when everything around us is telling us to prove our worth to the rest of society.

Which brings me to these work phenomena I mentioned at the beginning. Could it possibly be that through the lens of the pandemic, some people are starting to see what rubbish our work lives have become over the last few decades? How the extraction is an unlivable, unsustainable practice for any resource, including us? We get to have boundaries between the parts of our lives that require labor in exchange for pay, and we get to say when we're unwilling to make unfair exchanges and trades. Maybe if we start with our own worth, we'll be more able to dismantle this false idol of "time is money."